D

How taking Pelvic Floor procedures outside the operating theatre can free up capacity

Kim Gorissen, Mahreen Pakzad, Rod Teo, Annabelle Williams

Waiting times for surgery have increased across multiple specialties in the COVID-19 era, but a particular challenge is presented by pelvic floor procedures, which are considered non-urgent and were thus commonly delayed to make room for other, more urgent surgery even before the start of the pandemic. This has resulted in some patients waiting months or even years for life-changing surgery, and COVID-19 has only made things worse.

One of the biggest challenges currently facing the clinical community is access to theatre and capacity for surgical procedures. New approaches are needed to free up space and to increase efficiencies. We will need to ensure these new approaches are introduced sensitively, and they will require training and support – but could form part of a long-term solution for capacity issues overall.

KEY POINTS

- Transitioning procedures, where appropriate, from general to local or regional anaesthetic in clean rooms or day-case theatres could free up space in operating theatres and help address the backlog of cases

- Care must be taken to ensure a sterile environment and technique, as well as to safeguard patient comfort

- Implementing a mentoring programme could help to make the switch efficient and smooth, without compromising patient safety or wellbeing

Going local: could local and/or regional anaesthetic be an option for some procedures?

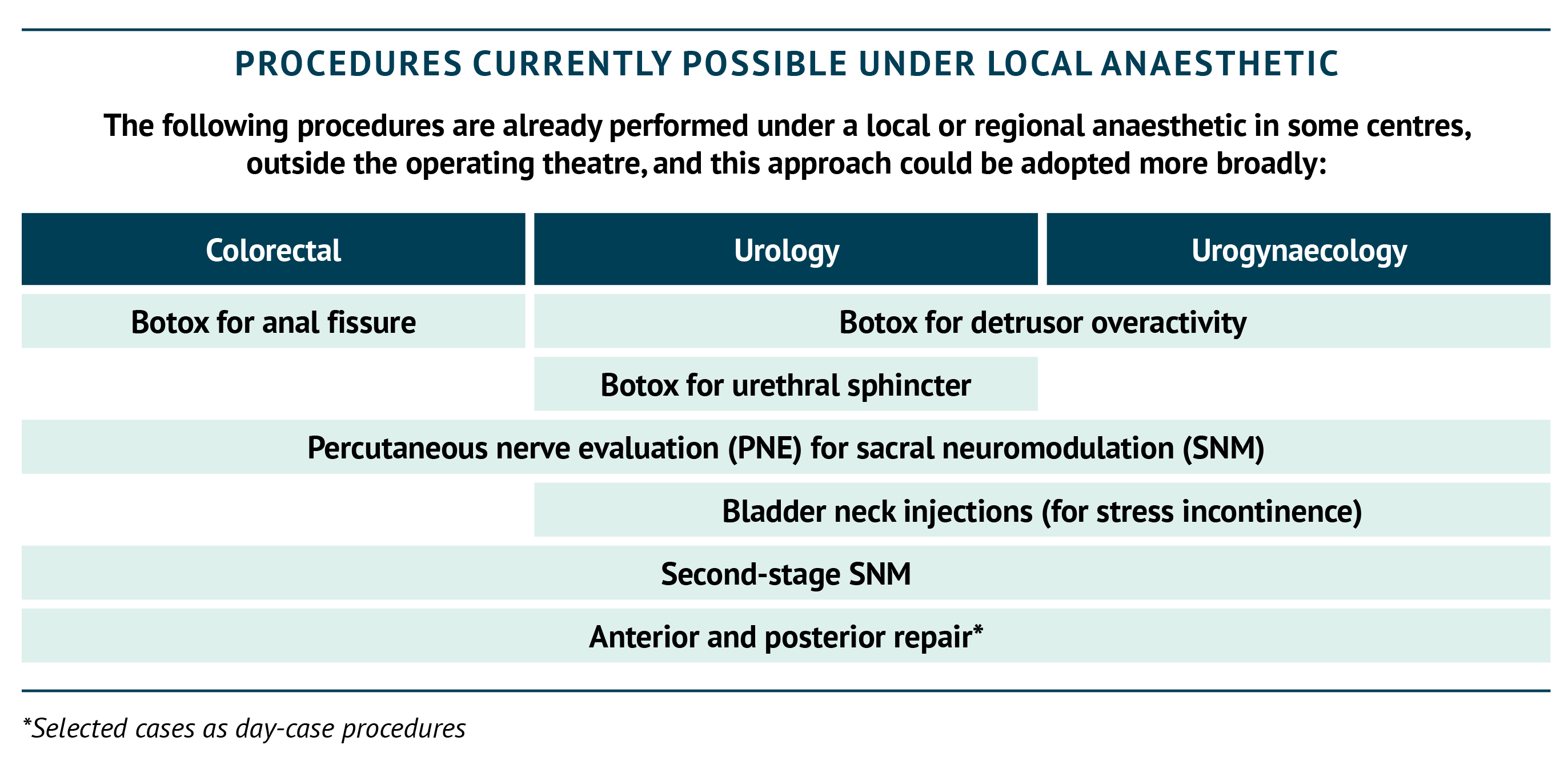

Transitioning from general to local anaesthetic (LA) for selected procedures may allow them to be performed outside of the operating theatre, in clean rooms (where the only anaesthesia that can be used is local, with the possible addition of some sedation). This would both reduce the wait for operating space for these procedures and potentially increase efficiencies by freeing up theatre space for other procedures. The box below includes examples of procedures that are possible candidates for this approach, and indeed already in use in some centres. Some changes may open the door to others; for example, where the first stage of testing for sacral neuromodulation (termed percutaneous nerve evaluation, PNE) is well established under LA, the second stage (battery implant) could lend itself to being performed under LA as well (Thompson et al., 2010). In carefully selected and fully counselled patients, tined lead insertion under LA could also be a consideration. Intra-urethral sphincteric Botox injections for voiding dysfunction can be delivered under LA in a clean room, taking them out of the main theatre suite. However, localisation of the sphincter needs to be guided by ultrasound or by concomitant urethral sphincter electromyography (EMG), if available.

Using regional anaesthesia (RA) for some procedures may also be an option to increase theatre capacity, as while this still requires the use of an operating theatre it deceases the interval required between cases – particularly during the COVID-19 era (Lie et al., 2020), where the aerosol generated by a general anaesthetic must be allowed to settle before the next case can commence.

There are important considerations to be aware of when considering a transition to local anaesthetic. Operating under local anaesthetic requires a different technique and specialised skills. Using sacral neuromodulation (SNM) as an example, highly experienced implanters are needed to minimise procedural interventions and ensure patient comfort during lead insertion and testing. Indeed, patient comfort should be the central consideration with the patient supported throughout the procedure by staff dedicated to do so.

Where and how can we perform the procedures?

Any clean room should be an option for a procedure under local anaesthetic where, in general, a sterile environment is still needed. A positive-pressure airflow system may be required, dependent on the procedure being performed. Technique should also be sterile to ensure patient safety.

In addition, day-case theatres in separate units might provide an option to move cases from busier centres to perform them under local or regional anaesthetic, freeing up theatre space. An added advantage of a day-case theatre is the reduced risk of being cancelled or delayed, in order to accommodate urgent procedures such as cancer surgery.

Some procedures – such as prolapse operations through the vagina – require as a minimum regional, rather than local, anaesthesia; in these cases, the operating theatre is still required, but the reduction in aerosol generation and the consequent time saved is an important consideration.

Further, some procedures may require general anaesthetic but could still be conducted as day cases. Laparoscopic ventral rectopexy has previously been conducted with same-day discharge with a high success rate – a single-centre UK study found 90% of patients were discharged within a day of the procedure (Powar et al., 2013). This approach could offer another route to reducing the burden on operating theatres.

Consideration should be given to the type of anaesthetic to be used: for example, spinal anaesthetic can cause urinary retention, so it is not appropriate for all patients. There is always a chance that the patient may have to be put under a general anaesthetic, so the patient will still need to be assessed and prepared accordingly. In the current situation patients need to be swabbed for COVID-19 and have a negative test result.

ENSURING A STERILE ENVIRONMENT FOR LOCAL AND REGIONAL PROCEDURES

The space in which the procedure is conducted must have:

- Appropriate positive-pressure airflow system,*

- Sterile, packaged equipment,

- Available intravenous antibiotics,

- Anaphylaxis kit accessible in the room.

- The usual behavioural approaches to ensure sterility must be maintained even outside the operating theatre.

*The number of necessary airflow changes will be procedure dependent.

What else should be considered in switching to local or regional anaesthetic?

Provision of anaesthetic team support can be a challenge. Fentanyl is a preferred IV pain relief option for some procedures when procedures are being conducted under local anaesthetic, but must be administered by a trained specialist (for example, a specially trained nurse). In the past, where sedation was not planned, there have been challenges in securing the assignment of specialist anaesthetic nurses. Such assignments could be beneficial to staff, offering them the chance to gain experience and help to set up new services.

Dialogue with the pharmacy to ensure such medications are available can be lengthy: in order to minimise disruption, these should be prioritised.

A mentoring programme could help to support Trusts and clinicians to make the switch where appropriate, without compromising patient safety or wellbeing. Once the switch has taken place, the service should be audited to ensure patients are comfortable and procedures are being conducted appropriately.

CASE STUDY: EVOLUTION OF APPROACH AT THE BRISTOL UROLOGICAL INSTITUTE

At the Bristol Urological Institute, the urodynamics-dedicated suite, which has its own C-arm and couch, has been used for the last 5 years to perform procedures that have been previously conducted in theatres. For example, the first stage (percutaneous nerve evaluation [PNE]) of sacral neuromodulation (SNM) has traditionally been conducted in theatres, either under sedation or regional/general anaesthesia in the United Kingdom, as it also requires image intensification/fluoroscopy. Now, however, it is purely being done under local anaesthesia with X-ray guidance, on an outpatient basis, reducing pressure on theatres. Equally, Botox, which used to be done in theatres, is now almost exclusively done in the urodynamics suite under local anaesthesia by a trained nurse practitioner, easing pressure on theatre and also on surgeons.

Injection of urethral bulking agent was also planned to be conducted on an outpatient basis, but the start of this service was halted due to COVID-19 and will now commence in the summer of 2021.

CASE STUDY: MANJIT’S STORY

A 22-year-old nulliparous woman with chronic urinary retention was diagnosed with Fowler’s syndrome and a high tone non-relaxing urethral sphincter. She was catheter dependent, and found urethral catheterisation very painful. She was offered all therapeutic options, including insertion of suprapubic catheter, a trial of sacral neuromodulation, a trial of intra-sphincteric botulinum toxin type A and also major reconstructive surgical procedures, such as Mitrofanoff and ileal conduit urinary diversion and stoma bag. She preferred the option of Botox as more of a reversible solution for her. Due to very high body mass index (BMI) and asthma, she was at high risk for general anaesthesia and the potential complications associated with it, e.g. deep vein thrombosis (DVT). In addition, she was surgically prioritised as an NHS England Category 4 patient, as she theoretically could wait at least 6 months, for her procedure and was also at risk of repeated deferment due to low clinical priority. She was offered the intra-sphincteric Botox option under LA and EMG guidance in a “clean room”, which she gratefully accepted, with significantly lower waiting time.

REFERENCES

Lie SA, et al., 2020. Practical considerations for performing regional anesthesia: lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Anaesth 67(7):885-892.

Powar MP, et al., 2013. Day-case laparoscopic ventral rectoplexy: an achievable reality. Colorectal Dis 15(6):700–706.

Thompson JH, et al., 2010. Sacral neuromodulation: Therapy evolution. Indian J Urol 26(3):379–384.