Introduction: The Reality

Steven Brown, Charles Knowles, Shahab Siddiqi, Carolynne Vaizey, Andrew Williams

What is a pelvic floor disorder?

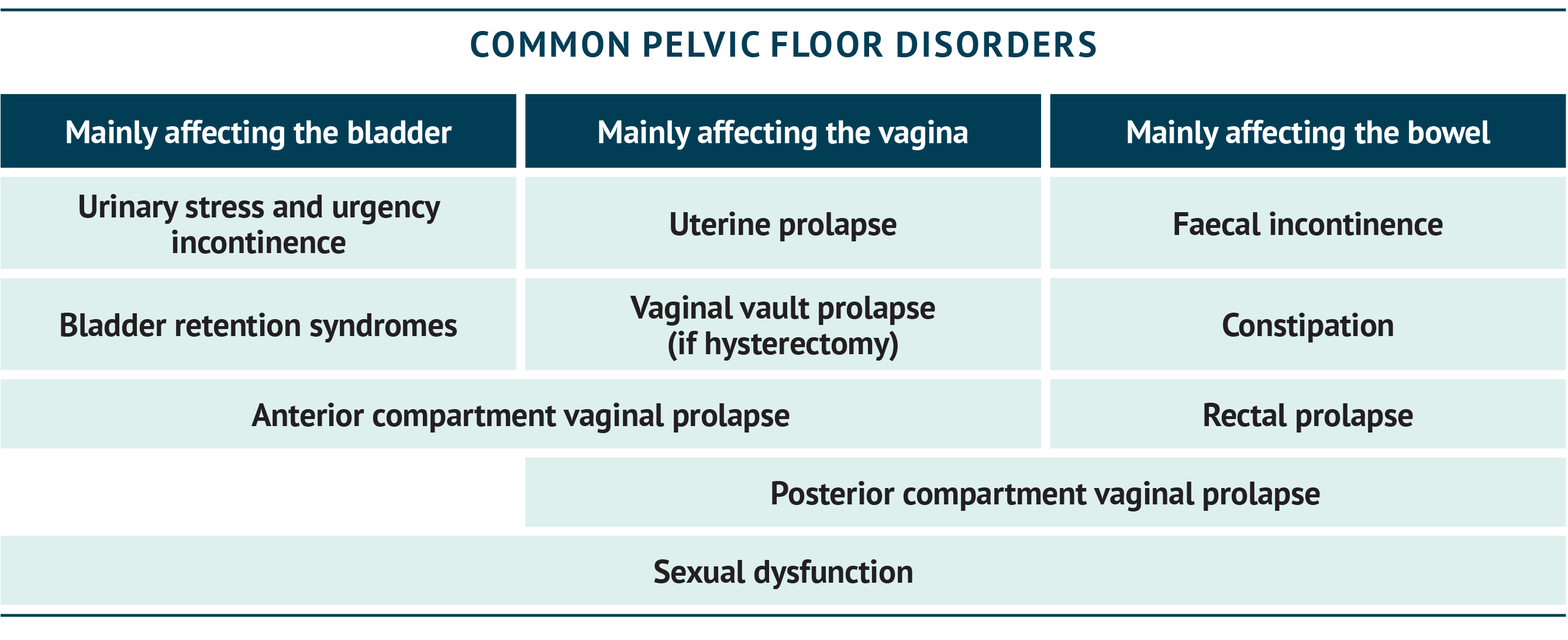

There is no particularly easy way to exactly define the parameters that constitute a ‘pelvic floor disorder’. Rather, the term is used as a catch-all for a number of conditions that primarily affect the bladder, lower bowel (anus and rectum) and vagina, and whose cause (at least in part) derives from a loss of support by the sheet of muscles that forms the pelvic floor itself. It is instructive to consider that the pelvic floor muscles together form a sort of ‘basin’ or ‘hammock’ to carry and contain the weight of these organs and maintain their anatomical disposition so that they function normally. While doing so, these organs must pass through openings in the pelvic floor to let things out (such as urine, faeces or babies) or in.

If the pelvic floor becomes weakened, stretched or injured directly, for example at childbirth, this normal support may be lost. This can lead to risk of obvious prolapse (organs visibly falling down), but more commonly to smaller changes in organ position such that these then do not function normally – either not emptying (for example, bladder retention or constipation) or emptying without control (incontinence). Perhaps counterintuitively, a lack of pelvic floor relaxation can also lead to problems such as constipation – this can occur with seemingly no trigger or may be related to conditions such as neuropathic pain, Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis. Sexual dysfunction may occur as a result of a weakened or overactive pelvic floor.

Since normal function is a feature of fine nerve and muscle control as well as gross structure, it is no surprise that pelvic floor disorders are common and often hard to treat. Imagine the act of defecation (evacuating the bowel) as an example – something most of us take for granted. This requires filling the rectum (from the colon), us being able to sense when it is full (sensory function) and then being able to push out the contents whilst opening and then closing the anus at an appropriate time. Remarkably, these functions also allow us to discriminate solid, liquid and gas and selectively expel gas from a mixture. This requires functions of the brain and spinal cord as well as the organs themselves.

Some of the main conditions falling within the remit of pelvic floor disorders are shown in the summary box below.

How many patients are suffering from pelvic floor disorders?

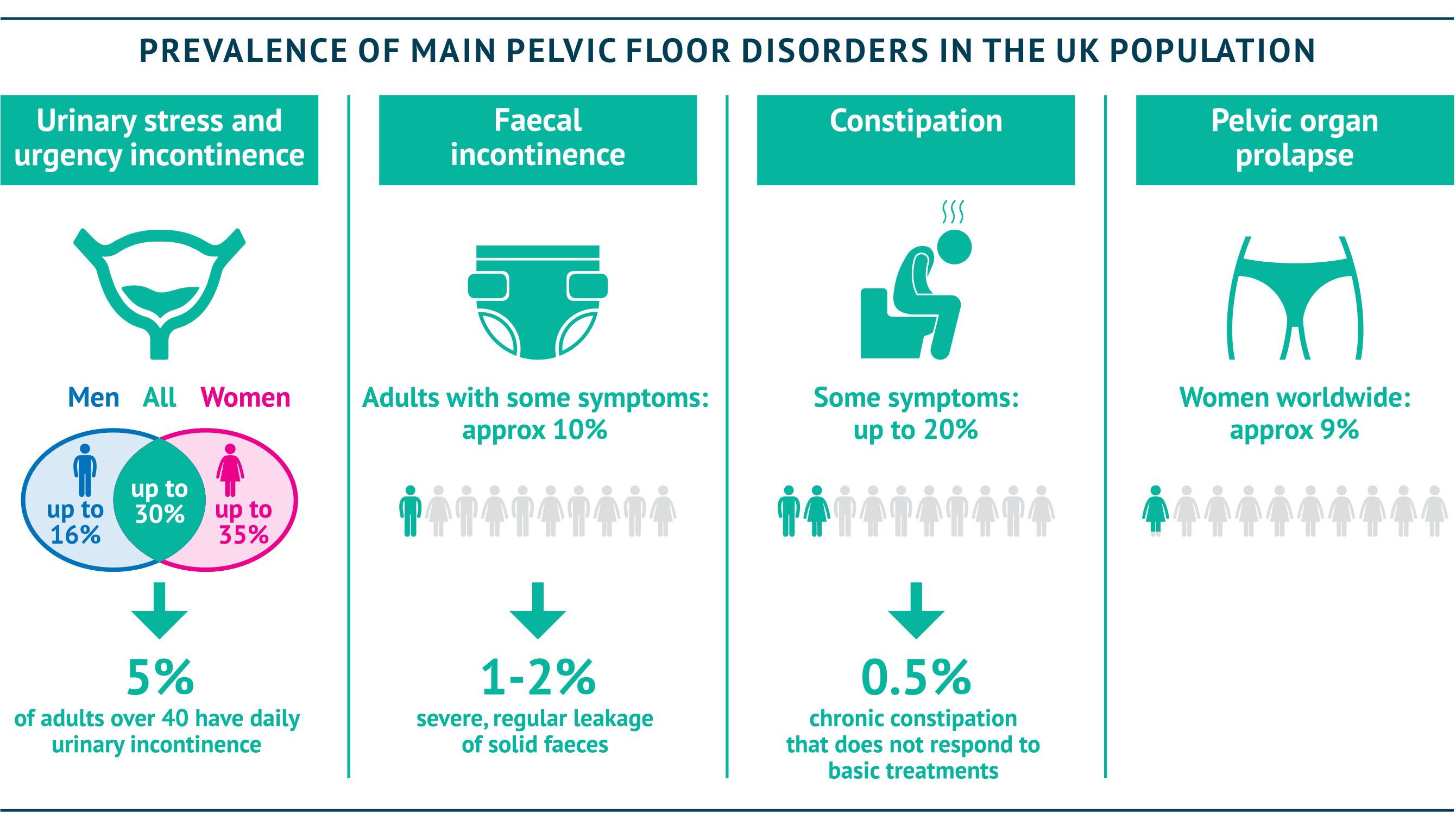

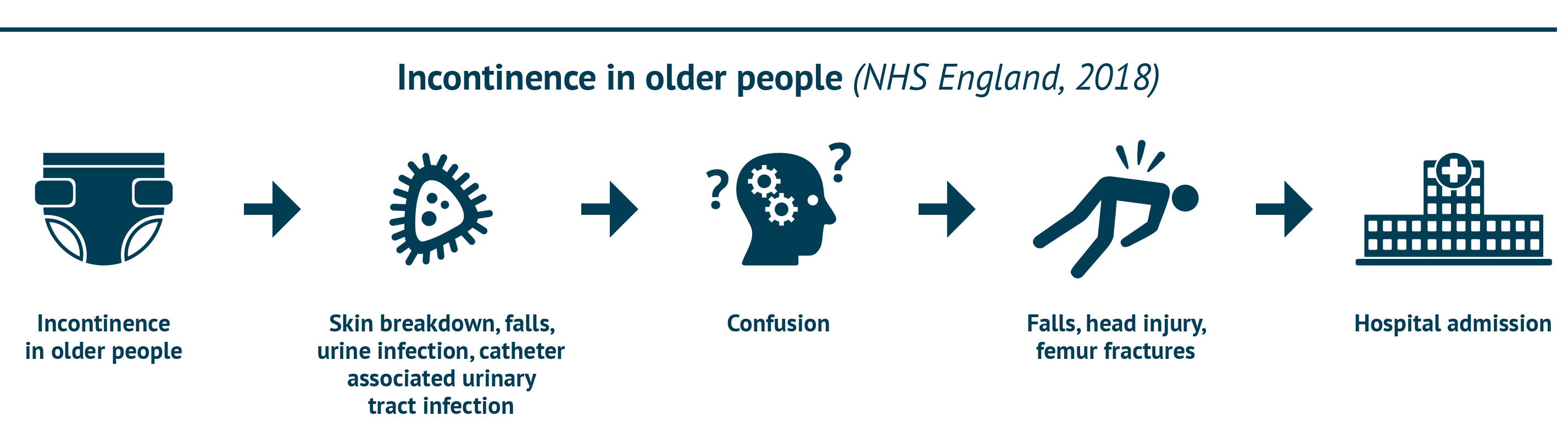

Whatever the cause of their condition, patients with pelvic floor disorders should be considered to be suffering from an invisible disability – and a common one, at that. The summary box shows key figures on how common some pelvic floor problems are – not far behind the common cold (Royal College of Surgeons, 2017; NICE Single Technology Assessment, 2013; Hunskaar et al., 2004; Downey & Inman, 2019; Boyle et al., 2003; Suares & Ford, 2011; Vos et al., 2012; Perry et al., 2000).

How are pelvic floor disorders treated?

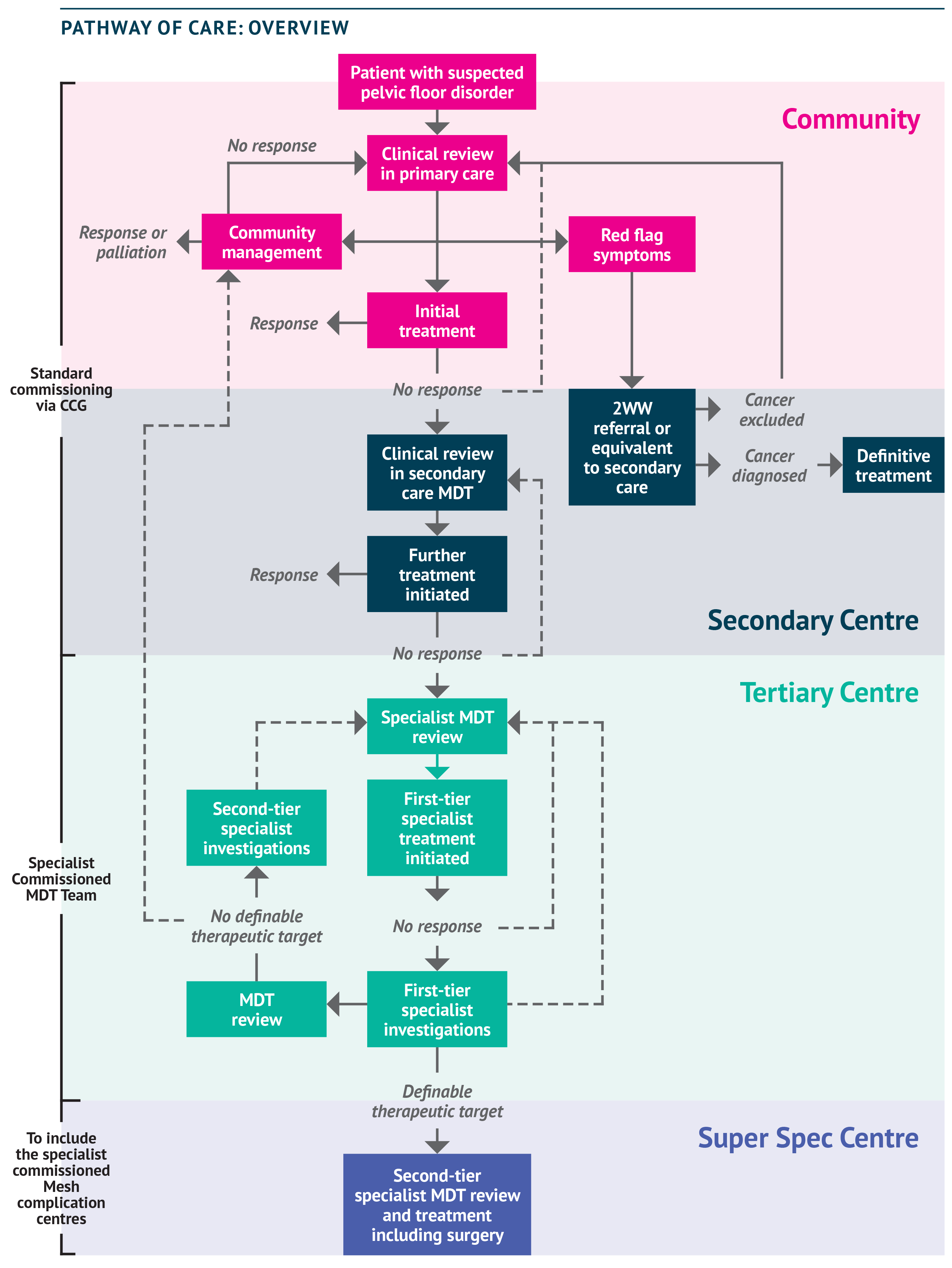

With so many people affected, including both men and women (and around 900,000 children and young people [NHS England, Excellence in Continence Care, 2018]), who manages these conditions and what is available? The figure below shows a schematic for a generic pathway of care that holds true for the majority of patients. The figure illustrates the many steps taken to get access to specialist care, and then the steps required once there to obtain and review specialist investigations, trial sequential therapies, and so on.

Given the number of steps involved, it is important to bear in mind that each visit to a hospital can require up to half a day’s travel and time at the clinic (ACPGBI Legacy Working Group, 2020) – not an easy ask, particularly as many patients are afraid to leave their homes because of their condition.

A wide range of clinical guidance is available on pelvic floor conditions, but there are gaps. There is a lack of clear guidance to support joined-up care between specialties for complex cases: guidelines tend to focus on a single compartment (for example, the NICE guideline on faecal incontinence [NICE guidelines, 2007]). The NICE guideline on faecal incontinence further lacks a focus on multidisciplinary team (MDT) working (NICE guidelines, 2007). There is no NICE guidance for constipation in adults or for daytime urinary incontinence in children. Guidance on pelvic floor dysfunction and non-surgical management is, however, in preparation for release in 2021 (NICE, 2020) and a revision of international guidance on the prevention and management of incontinence (urinary and faecal) will be available in late 2021 (International Continence Society, 2020).

Updated guidance is important; however, additional steps must be taken to address the challenges faced in implementing that guidance in the current environment. At present, patients face a number of access issues, including problems with obtaining referrals. There is, for some patients, a lack of appreciation by clinicians in primary and secondary care of the complexity of their pelvic floor issues, and this can mean the right questions are not asked in order to take an accurate history (Vollebregt et al., 2020). There is a lack of guidance for patients on experts who can be consulted before going to hospital – for example, specialist pelvic health physiotherapists, continence nurses and other sources of support available in the community – and when patients do reach a hospital, they can find themselves stuck in a ‘loop’ of repeated assessments by inappropriate specialists.

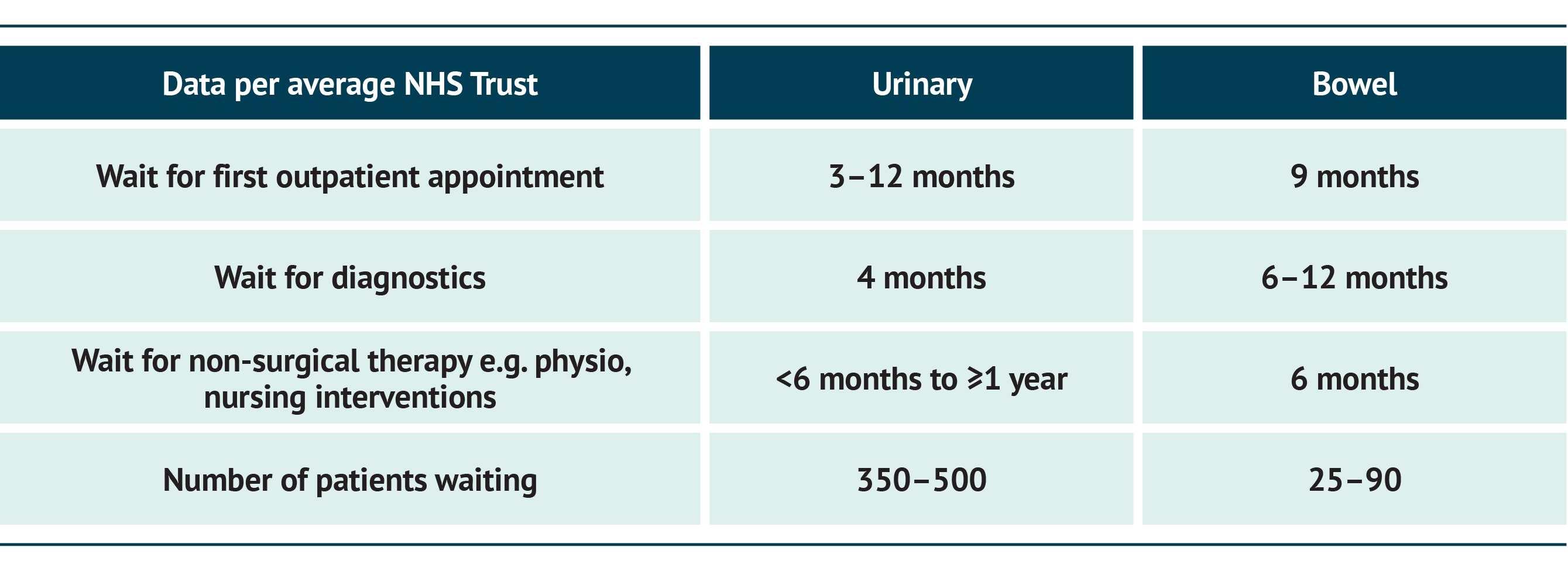

Waiting times for referrals and then for subsequent treatments are long. Some patients have been waiting years for their disorder to be treated. Accurate data are not available but a number of pinch points in the above pathway related to hospital care can be highlighted by data from a survey of the authors.

These waiting times vary across the country: the services and support available to patients are fragmented across the UK, with occasionally sizeable differences in care in different regions. However, overall the data paint a picture of years rather than months of waiting to access definitive care. This clearly indicates a need for resources to be directed towards developing a larger, suitably skilled workforce, including AHPs and specialist physicians.

Patients with pelvic floor problems, already experiencing high rates of depression and anxiety (Vrijens et al., 2017), have found their situation worsened further by the delays and isolation resulting from COVID-19. Mental health support for these patients is underfunded nationally; however, psychological support is necessary even on a short-term basis until they are able to undergo surgery. There is a national shortage of clinical psychologists (British Psychological Society, 2019), although some Trusts have mental health support available for birth trauma (Birmingham and Solihull NHS Foundation Trust). A clinical psychologist is needed in every unit dealing with benign disorders in line with the NHS Long-Term Plan (NHS England, 2019) and CQUIN guidance for 2020/21 (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2020).

CASE STUDY: JANE’S STORY

Jane suffers from interstitial cystitis, which is a bladder condition that causes long-term pelvic pain and problems with urinating. For over three years, her local hospital Urology team has been administering sodium hyaluronate every six weeks – although she still had flare-ups, the treatment meant that she could keep working and living largely as normal.

After a round of treatment in February, the onset of COVID-19 led to cancellations of her appointments until further notice. With no regular therapy, she found her flare-ups increased in frequency and lasted longer. By September her life had become so heavily impacted that she found it difficult to leave the house, and suffered from tiredness and low mood as a result of nights disturbed by the need to visit the toilet. The pain and burning sensation were persistent. Finally, after a particularly bad night, she found the Bladder Health UK website and phoned their Advice Line. The advice she received led her to contact her Urology Team’s secretary, and she found that treatments were recommencing – finally, she was able to restart treatment, but the delay meant her condition had worsened and she now needs four-weekly, instead of six-weekly, treatments.

Jane’s symptoms have finally calmed down, but with COVID-19 cases on the increase she is fearful of more cancellations and once again having to endure a recurrence of her symptoms – a physically and emotionally draining situation.

Why should we act now?

Post-COVID-19 waiting times are becoming even worse as patients are de-prioritised further in overloaded health systems (FSSA, 2020). A recently released report from NHS England and NHS Improvement estimated that around 4.5 million people were waiting for non-emergency treatment in November 2020, with almost 200,000 having waited for over a year (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2021). Patients with continence problems, who have already been isolating for years, now find themselves at the back of an even longer queue.

Although it has made the situation worse in many ways, COVID-19 has also provided evidence that change is possible. Across the NHS, new ways of working have been introduced at unprecedented speed, including movement of services and acceptance of technology and telemedicine (ACPGBI Legacy Working Group, 2020). The pandemic has also exposed some poorly thought-out systems and practices, which we now have an opportunity to improve.

Pelvic floor services are uniquely positioned to take advantage of advances in technology and integrated care organisations owing to the multidisciplinary input required – coordination of multiple specialists has previously caused delays, but telemedicine should in theory make this easier to implement. Technology-enabled care may, in the short term, also help us to address shortages in the workforce and to improve services for patients, including remote assessment and follow-up and even online group support sessions for patients.

Medicine will never be the same after COVID-19; a lot of us, myself included, are converts to telephone assessment and remote access, whereas I never thought it would be possible to assess a pelvic floor patient over the phone”

Andrew Williams, Past President, Pelvic Floor Society

We must acknowledge that our workforce is finite; taking another look at how we assess and treat patients can help to simplify patient pathways and reduce duplication. Integrating pelvic floor care is critical for those patients with multiple compartment issues. In primary care and the community, initial pelvic floor assessment and therapy by a specialist pelvic help physician will address all aspects of bladder and bowel symptoms in a patient-centred programme. This approach could be replicated throughout the patient pathway to ensure joined-up care.

Multi-speciality services and MDTs are critical for patients with complex needs and present another area where technology can help, by connecting expertise. A hub-and-spoke approach with regional pathways will allow regions to make the most of existing expertise and capacity. Further, reconsidering where procedures are performed, and by whom, can free up staff and reduce the backlog. Some procedures can be moved from the operating theatre to a clean room, and protocol-led procedures could allow specialist nurses to take more of a role here. Creative approaches, such as making use of available resource in the private sector, could also help to address capacity issues.

It is important to recognise the importance of developing a future workforce: increasing training opportunities and courses is essential to promote career development in pelvic floor disorders, and thus to develop new specialists to replace the current workforce, as needed. Continence care for all ages should be included in the medical school curriculum, yet a recent survey found that 14% of UK higher education institutions with healthcare programmes offered no content at all around incontinence; in those institutions where continence was covered, the number of hours devoted to this ranged from 2.5–7.3 hours, across three years (McClurg et al., 2013). Around 80% of institutions reported no improvement or even a decrease in provision in the prior five years. Only 6% covered continence in a dedicated module (McClurg et al., 2013). Yet education of non-pelvic-health-specialist HCPs, particularly GPs and nurses, is critical to ensure they are aware of the severity of these conditions and of how to treat, advise and refer patients. Post qualification, specialist training is also under pressure: the loss of biofeedback courses nationally within colorectal care is particularly concerning.

CASE STUDY: MINIMUM STANDARDS FOR CONTINENCE CARE

In 2014, the UK Continence Society published a set of minimum standards for care covering service specification, education and training required to deliver adequate care (UKCS, 2014). This document includes recommendations for multidisciplinary education of HCPs as well as the involvement of multidisciplinary teams for specialist assessment. The aim of this report is not to replace but rather to complement these minimum standards, which in many cases are yet to be met.

Finally, we need to ensure we empower and educate patients and health professionals so that they are aware that pelvic floor disorders are not a normal part of life and can be treated. Access to treatment should be clearly signposted, including the availability of local services and conservative treatments prior to the last resort of surgery.

The practical proposals in this report address three key gaps highlighted by the NHS Long-Term Plan (NHS England, 2019): funding and efficiency, health and wellbeing, and care and quality. A further consideration is the opportunity for specialist commissioning: it may be possible to take another look at the funding model for the different tiers of treatment. Specific issues with individual procedures, such as mesh insertion, are beyond the scope of this report and have been well covered by the recent inquiry headed by Baroness Cumberlege (Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review, 2020). However, a revised approach may help to address these further. More information is also available in the recent NICE guidelines on urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women (NICE guidelines, 2019).

Ultimately, NHS resource is finite and the difficult job of balancing priorities and funding is a sizeable challenge. In this report, we include a mixture of recommendations, including those that should be actioned at a national level (and therefore require additional or re-allocated funding) as well as a number of practical steps that can be taken by medical colleagues and management teams within Trusts in order to effect positive change quickly. In particular, we hope to highlight ways in which teams are already doing things differently, to inspire and encourage others.

READING THE REPORT

The recommendations in this report are divided across six main themes:

- Chapter A: Awareness and education

- Chapter B: Technology-enabled care

- Chapter C: Integration of expertise

- Chapter D: Surgery procedures and premises

- Chapter E: Utilising human resource

- Chapter F: Novel approaches to freeing up resource

Taken together, we firmly believe that the recommendations in this report will support improvements in care that will transform the lives of patients with pelvic floor disorders. To change lives, we must first change the system.

The time to act is now.

REFERENCES

ACPGBI Legacy Working Group, 2020. Legacy of COVID-19 – the opportunity to enhance surgical services for patients with colorectal disease. Colorectal Dis 2020; doi: 10.1111/codi.15341. (Online ahead of print.)

Baroness Cumberlege, 2020. First Do No Harm: The report of the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review. Available at: https://www.immdsreview.org.uk/Report.html (last accessed September 2020).

Birmingham and Solihull NHS Foundation Trust. Perinatal mental health service. Available at: https://www.bsmhft.nhs.uk/our-services/specialist-services/perinatal-mental-health-service/ (last accessed September 2020).

Boyle P, et al., 2003. The prevalence of male urinary incontinence in four centres: the UREPIK study. BJU Int 92(9):943–947.

British Psychological Society, 2019. Addition of psychologists to shortage occupation list highlights need for more training. Available at: https://www.bps.org.uk/news-and-policy/addition-psychologists-shortage-occupation-list-highlights-need-more-training (last accessed September 2020).

Damon H, et al., 2006. Prevalence of anal incontinence in adults and impact on quality-of-life. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 30, 37–43.

Downey A, Inman RD, 2019. Recent advances in surgical management of urinary incontinence. F1000Res; 8:F1000 Faculty Rev-1294.

FSSA, 2020. Clinical Guide to Surgical Prioritisation During the Coronavirus Pandemic. Available at: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/coronavirus/surgical-prioritisation-guidance/ (last accessed October 2020).

Hunskaar S, et al., 2004. The prevalence of urinary incontinence in women in four European countries. BJU Int 93(3):324–330.

International Continence Society, 2020. Update on Novel Coronavirus. Available at: https://www.ics.org/2020/about/coronavirus (last accessed March 2021).

Irwin DE, et al., 2008. Symptom bother and health care-seeking behavior among individuals with overactive bladder. Eur Urol 53(5):1029–1037.

McClurg D, et al., 2013. A multi-professional UK wide survey of undergraduate continence education. Neurourol Urodyn 32(3):224–229.

Milsom I, et al., 2001. How widespread are the symptoms of an overactive bladder and how are they managed? A population-based prevalence study. BJU Int 87, 760–766.

NHS England, 2019. The NHS Long-Term Plan. Available at: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/ (last accessed September 2020).

NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2020. Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN): Guidance for 2020/2021. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/commissioning-for-quality-and-innovation-cquin-guidance-for-2020-2021/ (last accessed September 2020).

NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2021. NHS referral to treatment (RTT) waiting times data. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/rtt-waiting-times/rtt-data-2020-21/ (last accessed January 2021).

NICE, 2020. Pelvic floor dysfunction: prevention and non-surgical management. In development [GID-NG10123]. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-ng10123 (last accessed October 2020).

NICE guidelines, 2007. Faecal incontinence in adults: management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg49 (last accessed October 2020).

NICE guidelines, 2019. Urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng123 (last accessed October 2020).

NICE Single Technology Appraisal, 2013. Lubiprostone for treating chronic idiopathic constipation: Final scope. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA318/documents/constipation-chronic-idiopathic-lubiprostone-final-scope2 (last accessed October 2020).

Perry S, et al., 2000. An epidemiological study to establish the prevalence of urinary symptoms and felt need in the community: the Leicestershire MRC Incontinence Study. Leicestershire MRC Incontinence Study Team. J Public Health 22(3):427–434.

Royal College of Surgeons, 2017. Commissioning guide: Faecal Incontinence. Available at: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/files/rcs/standards-and-research/commissioning/commissioning-guide-for-faecal-incontinence-final-january-2014.pdf (last accessed October 2020).

Suares NC and Ford AC, 2011. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic idiopathic constipation in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 106(9):1582–1591.

UKCS Continence Care Steering Group, 2014. Minimum standards for continence care in the United Kingdom. Available at: https://www.ukcs.uk.net/resources/Documents/15091716_Revised_Min_Standards_for_CC_in_UK.pdf (last accessed April 2021).

Vrijens D, et al., 2017. Prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms and their association with pelvic floor dysfunctions-A cross sectional cohort study at a Pelvic Care Centre. Neurourol Urodyn 36(7):1816–1823.

Vollebregt P, et al., 2020. Coexistent faecal incontinence and constipation: A cross-sectional study of 4027 adults undergoing specialist assessment. EClinicalMedicine 000:100572 (epub ahead of print).

Vos T, et al., 2012. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380(9859):2163–2196.